How to flashcard

This guide is meant to summarize some specific steps that one can take to effectively flashcard for quiz bowl.

Flashcarding is only one facet of studying and certainly not a requirement for playing, improving, or enjoying quiz bowl - for a broad overview of other approachs, see How to study and read the guides in the "Study" page.

Overview

There are only a few steps involved in effective flashcarding (henceforth referred to as "carding"). In order of importance, they are:

- Reviewing cards with regularity

- Creating new cards

- Amending old cards

There is also a zero-th step, which is "Obtaining a carding program." This guide will start by summarizing each in chronological order from "card creation" to "card retiring".

Many other players have described their personal preferences with carding - you will likely find many of their insights productive to read through. A few are listed here:

- So You Want to Study Quizbowl - the classic guide by Max Schindler

- Re: Help studying by AGoodMan - advice from Jon Suh

Obtaining a carding program

For many players, the first experience they will have had with flashcards is something they wrote on physical index cards to remember vocabulary words or key terms for one of their classes. Even this rudimentary system is very effective, but its most significant drawback is that it does not scale. As the number of cards increases, the overhead of keeping them organized grows enormously. Quizlet, probably the best-known flashcarding software, allows the creation of digital questions on their website. This solves some of the organizational issues and many players may have started with this instead of physical cards. Both of these will suffice but suffer from the subtle issue that reviewing in order is not as effective as reviewing randomly, and both are less effective than an intelligent spacing.

For this reason, most players will recommend a software that makes use of "spaced repetition". This is a family of algorithms that decide to will delay showing you specific cards that you previously performed well on. There are two major programs which are used for this purpose:

| Anki | Mnemosyne |

|---|---|

|

|

| Shared features | |

| |

It is strongly recommended that you download one of these programs before you start seriously carding.

Downloading either of these free programs takes seconds on a typical internet connection. They are both perfectly acceptable choices - I (Kevin Wang) used Mnemosyne while I was in high school and switched to Anki in college, which I still use today. I would say that the only significant difference is that Anki has an iOS app - $25 well spent.

Creating new flashcards

The main goal of carding is to retain pieces of information. This begs the question of "where do these pieces of information come from?"

Typically, carding is a single, typically late, step of a studying pipeline. Clues are obtained from various sources, including packets or reference materials like textbooks, before being written down and eventually converted into flashcards.

It is possible to inherit a deck of cards (from a teammate, from a competitor, from online). You are certainly welcome to use these, but I caution you - the process of creating flashcards can be as significant for retention as reviewing them. It is very hard to beat someone to a fact with a card that they made.

Reviewing flashcards with regularity

Regularity is key.

Programs using spaced repetition will schedule specific cards to be reviewed at specific intervals from when they were reviewed - a card that was successfully answered on Tuesday may be scheduled for Friday, while one which took two tries may be slated for tomorrow.

Regularity is key.

Going through all of your due cards every day will ensure the maximum benefit from the algorithm. More practically, if you don't do your reviews one day you'll have to do them the next so try to avoid letting the backlog getting to big.

Regularity is key.

Improvement in any activity is dependent on prolonged, dedicated effort - having a program tell you exactly how much to do each day is just one manifestation of this.

Amending old cards

At every stage of the carding process, it is important to remember that cards are tools meant to improve retention. If you are repeatedly failing to answer a card correctly, it is useful to spend a moment considering whether you truly have not learned the material or if the card has been constructed poorly. Sometimes, it is even appropriate to judge that a card that you wrote is of no utility at all and simply discard it.

Some things you might do to a card in the middle of a review session:

- Add additional clues on the front to give more context

- Give more information on the back to act as a reminder

- Reorder the words to make it easier to parse

- Correct a factual error

- Mark it as an issue and return to it later

Tips, tricks, and aphorisms

Learn the types of cards

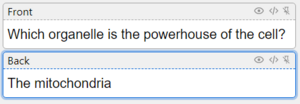

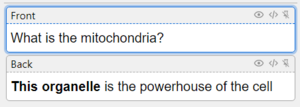

The simplest possible flashcard is the front-back - a piece of information on one side evokes a piece information on the other. This is likely the format you associate with flashcards, but it is far from the only kind. Knowing the different varieties (or even building your own) can improve your productivity.

There is a technically distinction between the card that you edit (called a "note" in Anki) and the cards you review (just called "cards"). In general, there is at least one card per note, but the precise mapping will vary from type to type. In most situations this difference does not matter and "card" can be used interchangeably.

| Type | Where this card shines | Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|

| Basic front-back

Your classic, vanilla, milquetoast flashcard. You read one side, think your answer, and flip to see if you're right - bing, bang, boom. The standard, both by default and by convention. Good for most situations. |

This card type is designed to retain simple associations: if A, then B. Basically any fact can also be distilled into this format, but some are particularly well-suited. A few examples:

|

The binary nature of this card type has a tendency to reify things in the mind of the user. Many clues considered "stock" can actually point to multiple answers when placed in different contexts or examined in more detail, so having cards which don't address this nuance can lead directly to negs.

Avoid this by fleshing out cards with context whenever possible - give extra information on the back or write full sentences on the front. |

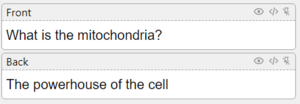

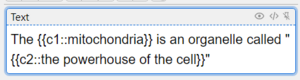

| Reverse front-back

One step beyond the basic, this card type can be reviewed in either direction. Each reverse front-back note has two cards - one for the front to back direction and the other for the reverse. |

One becomes good at what they practice - if one only has cards from A to B, it is much harder to go from B to A. These cards are useful for training that reverse direction. | There are very few true "binary associations" in quiz bowl. The classic use case for this card would be "word" and "translation" in language learning and most good uses have a similar pattern. One example use could be "technical term" and "definition".

There has to be enough context on both sides for them both to function, which means twice as much effort per note. |

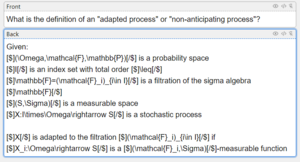

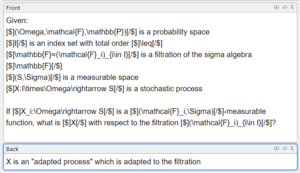

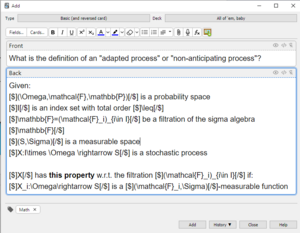

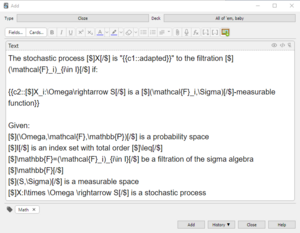

| Cloze deletion

Clozes (CLOSES) provide a convenient way to generate a large number of cards from a single note. An arbitrary number of sections of a text can be marked as a "cloze" - for each one, a card will be created that obscures that section and reveals it on the back. The preferred card type of science players. |

The strongest advantage of clozes is that they remove the need to copy-paste information while creating related cards, making them much faster to produce large numbers of. They are an efficient way to create cards that aim to capture how pieces of information interact, as well as for testing long lists of information. Very useful for retaining clues around the clue that the card is focusing on. | Because every card is derived from a single note, slight issues in how the initial text is phrased can make the resulting cards very confusing. This can be mitigated somewhat by adding notes to a cloze to give context, like the pronoun that an answerline would have or a hint. |

| Image occlusion

Conceptually very similar to clozes, but rather than selecting regions of text you select regions of an image. This is typically used for labeled diagrams to combine an image with a This form of card is supported in both Anki and Mnemosyne, but only through mods (for Anki and for Mnemosyne) |

This card type shares many advantages with clozes, but with one large addition: it is generally harder to manipulate images than text. Clozes can fairly simply be replaced with basic front-back cards, but the same is not true of occluded image cards - it is impractical to achieve the same results that the add-ons provide. | This type of card only works if you have an image on hand which a) is labeled and b) tests something meaningful. |

Some of the flashcard types described above perform similar roles. Two quick examples:

| Short note | Long note | |

|---|---|---|

| Card type | Note(s) | Note(s) |

| Basic Front-Back |

|

|

| Reversed Front-Back |

|

|

| Cloze |

|

|

The above images were taken in Anki.

Some analysis:

- The basic card type is not well suited for this kind of information. In the simple case, it requires roughly twice as many characters as the reversed front-back card and almost four times as many as the cloze.

- The reversed front-back card type is much better at creating this kind of card. The major downside is that there has to be extra context provided for the reverse direction. However, this information also makes it more obvious what is being asked for.

- The cloze shortens the amount of time required to write the cards but at the cost of some confusion, which is clear in the larger.

- In the simple scenario, the reversed front-back is probably the best but none are particularly far behind - even making two basic cards is quick. Clozes are technically the fastest but they're a little confusing to review.

- In the long scenario, the basic card becomes clearer than the reversed front-back and the utility of the back card is so small that one could probably omit it entirely. The cloze does okay, but its real strength begins to shine through this toy example: adding additional cards for other key terms is as simple as editing the card and selecting the new terms. To replicate this behavior with the other card types would be incredibly difficult.

Efficiency matters

Flashcarding is a long-term strategy - while it can be used for brief, intense study binges, most of its utility comes from its ability to provide results over the course of months of years. As such, it is important to try to save time whenever possible.

| |||

| Above: xkcd comic 1319 |

|---|

There is a point where trying to make a task more efficient costs more than just doing it. For instance, you may be tempted to implement your own Anki/Mnemosyne add-on to facilitate your unique workflow. At that stage, it is important to recognize that you've probably crossed the threshold and stop (and perhaps consider a career as an engineer).

Don't memorize shapes

The human mind is amazing - you may not believe it, but it is entirely possible (and quite common) to subconsciously remember the exact layout of the text on a card and use that to recall the answer. Remember: the goal is not to answer the most cards but to successfully retain the information.

Always try to read through the text of your card and process what it says before you

Bad cards produce bad buzzes

In computer science, the phrase "garbage in, garbage out" is used to describe the results of providing low quality or otherwise flawed data into a system. The principle holds true in many domains.

Some examples of bad cards:

| A bad card | Explanation | A better card | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

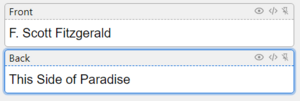

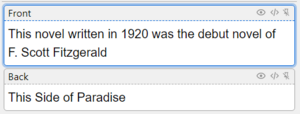

|

This card suggests that if a player hears "F. Scott Fitzgerald", they should assume the question is referring to the novel This Side of Paradise. This is a faulty association on several levels:

|

|

This card now gives a pronoun and uniquely identifying information. |

Employ shortcuts

| |||

| Above: xkcd comic 1205 |

|---|

Anki has various keyboard shortcuts - Mnemosyne does as well. Learn them and learn them well - saving a second every time you type in a cloze or put text in bold saves huge amounts of time over hundreds (or thousands) of notes.